📝 days 285-306: damascus (the first time)

Er is een Nederlandse vertaling van dit stuk gemaakt door Fleur - 🔗klik

Ironic. For my project dedicated to a borderless world, I seem to gravitate towards them for organising this blog. There’s a blog post dedicated to my 📝🔗2 months in Türkiye, then an 📝🔗entry for Lebanon, and here is one for Syria (although I will only be speaking of Damascus, since that’s the only place I actually visited). I wish I’d know another way of structuring my experiences on this blog, one that doesn’t use ‘borders’, but I haven’t come up with one yet. The harsh reality of our current world is that borders shape how we experience it, our relations to one another, and even our relationship to ourselves (I echo 📕🔗Harsha Walia here). In the case of Syria, the ideas of nation-states and borders determining reality, certainly applies. Thus:

welcome to this blog post about my 3 weeks in Damascus, Syria.

Old Damascus quarters

Damascus, together with Aleppo, claims the title of ‘oldest continuously inhabited city in the world’. When walking around the old parts of town, you feel this in everything. This city is old.

Even though 3 weeks is a short amount of time, I’m dedicating an entire blog entry to Damascus. I became enchanted by Damascus and its inhabitants. In the months since I left I talk about it all the time; it was that special. So, a full blog post only makes sense.

🗺️ syria shouldn’t exist (how europeans have a thing for making the world a worse place)

The current Syria is a strange creation. Admittedly, it shouldn’t exist, at least 📰🔗not in its current form. ‘Syria’ has historically referred to a region also comprising of parts of: current Türkiye, (currently occupied) Palestine, Lebanon and Transjordan. It was called Bilad Al-Sham (the land of Greater Syria). In the early 20th century the British and French carved up the region, chopped off parts that historically were part of Greater Syria, and divided the country along sectarian lines to ensure sectarian conflict. If different ethnic groups are fighting each other, a nationalist movement that threatens your colonial rule is less likely to take root. The Europeans first make the world, and then make the rules that govern it.

When I was 18 years old, me and my high-school best friend 🎥🔗Willem (you’ll like this link), wrote our big final high school report on Syria. It wasn’t particularly good: we didn’t know how to do any actual research, but we tried to gauge what factors caused the Arab Spring to morph into its years-long conflict. Ambitious, eh? We even got so far as to talk about British colonial rule carving up the country, pitting the sects against each other, and ensuring instability. We were on the right path! Our mark was 7.5 (out of 10). My fascination for Syria started then.

the fall (of a regime so dark it exceeds your worst nightmares)

📝🔗While at Europe’s border to Türkiye with No Name Kitchen, surrounded by (mostly) Syrian boys, we celebrated the fall of 53 years of Assad dictatorship. First Hafez and then his son (who should’ve been a dentist in the UK) terrorised the country with one of the most intense Soviet-style dictatorships of the 21st century. The Mukhabarat (secret police) ensured that political action was frozen and isolated before it could thaw and threaten power. Then, in December of 2024, I relished in the buzz among our Syrian friends in the Bulgarian refugee camp when an opposition coalition called ‘HTS’ took city after city, defeating Assad’s army. Then Assad took a plane to Russia and his government was over. I tentatively joined in the dancing and cheering, knowing full well that well that the new man taking Assad’s place was a former Al-Qaeda leader, and that the future was far from certain. More on that later.

Regardless, lively conversations in the camp were held about whether to continue the journey to dream destinations like the UK, Germany and The Netherlands, or turning back to the newly liberated Syria. Most people decided to continue their journey. For me, it meant that visiting Syria was suddenly possible without a government-appointed travel agent following me around. Half a year after Assad’s fall, I set off towards Syria.

Heidi and me having just entered Syria

The driver of the car behind us stopped to welcome us. He took this photo.

While still in Beirut I teamed up with 👤🔗Heidi Pett, an Australian journalist who had been in Syria in the months after Bashar al-Assad fell to report on the massive change. She was keen to cycle across the border, and stumbling across her which was very lucky, as cycling into Syria wasn’t the most popular endeavour. In fact, as far as I could tell, we were the first people to cycle into Syria from Lebanon since the fall, and probably the first ones since before that too. The ride went smoothly, and upon cycling into the country, we saw Syrian gardeners shape bushes on the side of the road, spelling out the English word ‘WELCOME’. The army stopped us then, shook our hands and with big smiles said what the bushes spelled out:.

“welcome”

As you’re starting to read about Damascus, I prescribe some Fairuz in your ears. Pro tip: whenever you meet somebody with Arab roots, play them some Fairuz and I guarantee you their eyes will light up.

initial observations

After having spent 5 weeks in the tense & charged city of Beirut, Damascus was surprisingly different. Here’s a few things I immediately noticed which you might not care about but which I think say meaningful things about Damascus as a city:

Damascus was a lot quieter than Beirut. Drivers honked less, and there weren’t diesel generators at every corner blasting the sidewalk with fumes.

There were traffic controllers on intersections and drivers actually obeyed them. Lebanon essentially is traffic anarchy (and not the good kind): half the cars don’t have (valid) license plates. Read my last blog post about this. Damascus was different: cars waited until a man in a cute suit waved his arm in the appropriate way.

Traffic was more sociable. As a bus driver and now-cyclist, I truly appreciate an empathetic traffic etiquette. Whereas Beirut was a total free-for-all, drivers in Damascus gave each other more space and patience.

Heidi and I made our way through the small and atmospheric streets of Old Damascus to the Christian neighbourhood of Bab Touma where there was a small guesthouse charging $20 per night (which, to my slight surprise, turned out to be relatively cheap for Damascus). Like the rest of old Damascus this building too almost couldn’t contain the amount of atmosphere held inside of itself. The house was clearly self-made, so every wall, window sill and staircase felt improvised, personal and heavy with history.

I’m not sure if I can convey to you how it feels like to be in a building that has been inhabited in some shape or form for hundreds if not thousands of years. It’s not something that I’m used to, coming from the swampy Netherlands and growing up in a hastily built 1970’s working class neighbourhood. The current purpose of the building was to be a guesthouse, but it must’ve undergone an almost infinite number of changes, with layers and layers of modifications, one on top of the other, making the current constellation of the building just that: the current one. Without a doubt the building would be modified in the centuries to come, perpetually shapeshifting to fit the needs of the current dwellers taking care of it. On the evening of our arrival I climbed to the roof, watched the sun set over the infinite array of roofs, and cried.

Half of the foreigners I met during my stay in Syria, I met in the few days I was at that guesthouse: a German yoga-lady (very sweet), an American woman with Lebanese roots looking for a corporate job (unsure why she chose Syria to climb a corporate ladder), and a handful more. It was from this guesthouse that I edited and posted a video to Instagram calling on people to become a sponsor as I was cycling into Syria. It worked, and with 500.000+ views and 54.000+ likes we rocketed to something like €250 per 100km going towards MiGreat and No Name Kitchen. That was pretty sweet. It showed me that internet strangers do indeed sign up to sponsor, even though they’ve never met me in real life (and consequently it showed me that growing an Instagram page can result in financial support fighting borders).

my damascus base (and the small hub of travellers)

Soon I realised though that $20 per night is pretty steep. Luckily for me I stumbled across Khaldoun on Couchsurfing. In his 40s, he’s a Syrian psychiatrist now treating a lot of former fighters with immense PTSD. A totally selfless figure who happily hosted any foreigner wanting to stay in his home. I got a dark, small, cool room, and other couch surfers either slept in his living room, his bedroom or in the guest room. At some point there were 5 foreigners sleeping in his tiny home. Khaldoun’s home became my 🗺️🔗base in Damascus. At Khaldoun’s place I met fellow Couchsurfer 👤🔗Maryam who became my Damascus travelling partner. She helped me film 🎥🔗this 7-minute video about The Palestine Laboratory (of which I’m very proud). Here are some things that we did:

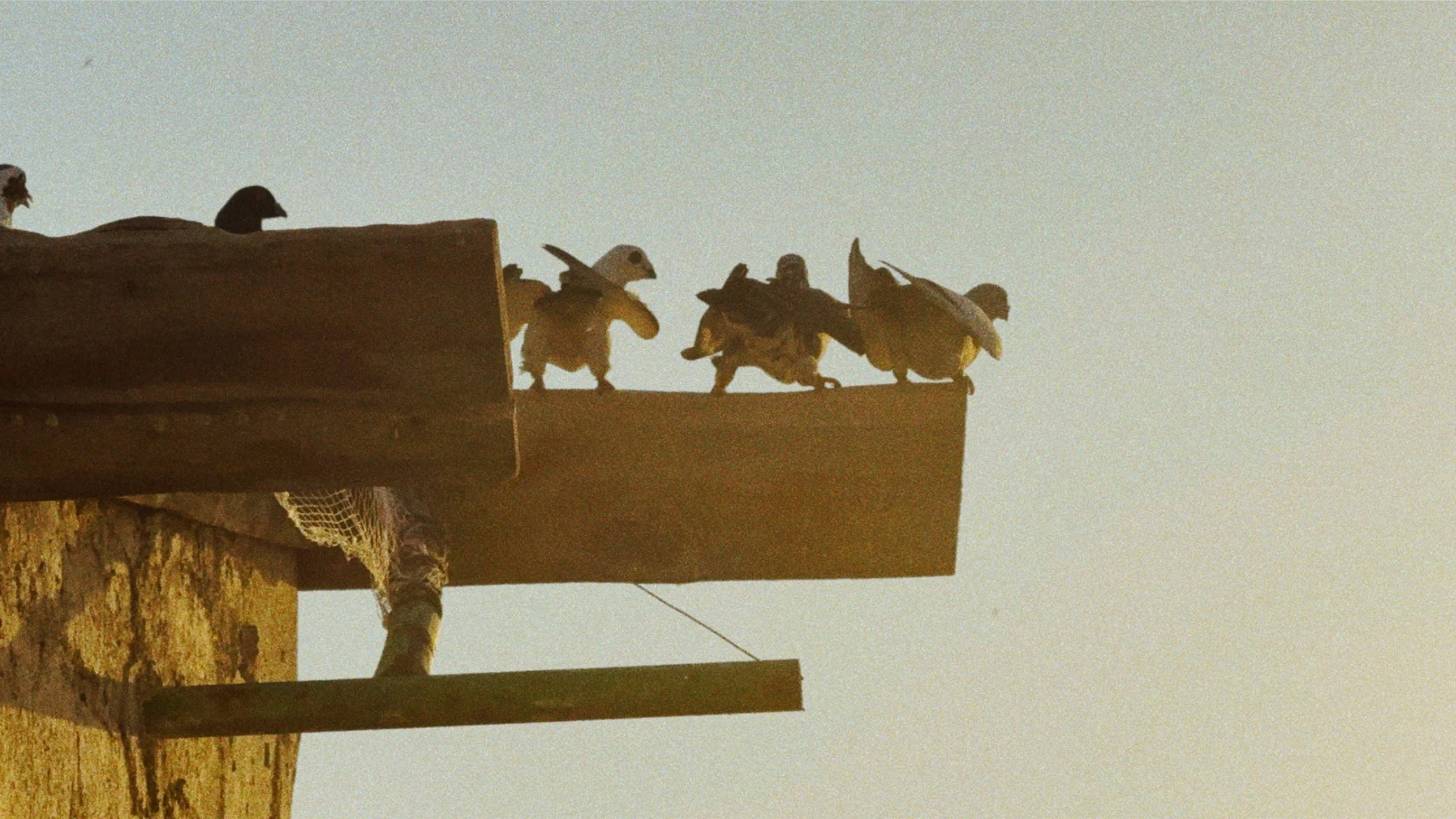

we saw pigeons on a rooftop

Fellow traveller 👤🔗Sarah charmed some men on the street to take us to their rooftop where they were flying pigeons around. The flock of pigeons flew around the rooftops of Damascus, and apparently the pigeon in the man’s hand is used to communicate with the flock. I didn’t totally understand but I was amazed at the sight.

we visited the destroyed Palestinian quarter of Yarmouk

The effects of war were not distributed evenly across the different parts of Damascus. For a very brutal episode of the war, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were besieged, bombed and starved in the Yarmouk quarter. The injustice suffered by the Palestinian people was laid bare: time and time again they bear the brunt of decisions made for geopolitical gain. Dispossessed from Palestine in 1948, communities fled to Yarmouk, unable to return home. Creating a flourishing community in Yarmouk, they were bombed and starved by the Assad regime first and then, in a cynical twist, by ISIS (who were probably let into Yarmouk by said government).

During the start of the uprising against Assad persecuted activists fled to Yarmouk - it was relatively safe there. The population almost reached 1 million by 2012. Now, in 2025, there live a few thousand people. Abu Saeed is running a Palestinian souvenir shop for the handful of visitors that come. Small shops are being set up again. For a video I’m quite proud of, watch 🎥🔗the thing I made about Yarmouk here.

chop chop barbershop

public traveller personas inevitably turn into propagandists (perhaps without realising it)

People who travel the world and show it to other people make for very effective propaganda outlets. I am one too; I show you a version of the world rooted in my deeply-felt anarchist principles, highlighting human solidarity in the face of injustice, and the common struggle toward liberation. All travellers are propagandists, no matter if you post videos about beach holidays in Bali or adventures traversing Mauritania on a cargo train.

Travellers have an immense reach as well. Hundreds of thousands of people consuming whatever they do and say. So if your wish is to polish up the image of your country, it can be as simple as getting a bunch of ‘Westerners’ to come (lure them with an easy and cheap visa), treat them well, and they’ll start saying all sorts of nice stuff. I currently see it happening with Afghanistan - travellers going there and showing off how well the Taliban is treating them - without laying bare the stranglehold the Taliban have on civil society, women, and popular resistance. It makes me feel uneasy.

I face the same danger in Syria. I was lucky enough to speak to a few queers in Damascus. They were frightened. Even though no new laws have passed explicitly targeting these things, they noticed bars restricting or stopping alcohol consumption, and even some bars closing earlier or shutting down entirely. Attacks on transgender people, especially transgender women, have increased and have reportedly been committed by the new government army. Homophobia is on the rise. One of my openly gay new Syrian friends is currently in hiding because there’s a mob hunting him.

We do have to concur with the fact that Ahmed Al-Sharaa, the new leader, has a background as an Islamist extremist. He was touted in Western media as a moderate leader, intending to protect civil liberties and pave the way toward democracy. But he already postponed elections by 5 years, his army is continuing to torture, rape and kill minority sects in Syria and no meaningful, concrete steps are being undertaken to stop it.

So, how to hold these two realities at once? The beauty that was Damascus, and the looming signs of more authoritarian rule? Should we refrain from visiting places like Afghanistan out of refusal to support the Taliban? But then where do we draw the line? Iran? Azerbaijan? The United States? What about witnessing and showing regular Afghani life, and the hotspots of resistance that do inevitably exist? These are open questions that I don’t yet have answers to. Perhaps they strike reflections in you, and if that’s the case, i’d really love to hear them. I put a form here for you, or leave a public comment.

the goodbye (for now)

During my cycle towards the Jordanian border I stumbled across a dilapidated small theme park. The image of a rollercoaster cart riddled with bullet holes is an image that evokes strong emotions, but it’s also the thing that makes me uncomfortable to show. In a lot of coverage of places like Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan war is presented as an inevitability. As something that “just happens” to these poor people living in these “volatile regions”. The supposed universal compassion that such images of bullet-ridden rollercoaster carts should evoke can often work to naturalise and depoliticise the roots of these conflicts. (much like ‘🎥🔗humanitarian work’ at borders)

Sadly, I must admit I don’t totally understand those roots. I must revisit 📕🔗The Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War to freshen up my understanding of the past 13 years of Syria’s brutal conflict, have heaps more conversations with Syrians, and even then, I don’t know if I’ll fully be able to grasp what made the past 13 years so brutal. For a blog that aims to give you my understanding of the current moment and what led to it, I have to disappoint.

🍉on my way to palestine (yallah habibis)

Luckily for me, I’m going to visit Damascus (and more of Syria) again soon. Given that:

Iran last month has effectively 🌐🔗made it impossible to freely cycle in the country (which came as a response to the hideous and unprompted attacks by ‘Israel’ and the US);

I want to avoid flying as much as possible (and thus can’t cross from Azerbaijan to Kazakhstan across the Caspian, as you can only enter Azerbaijan by air), and;

I don’t wish to travel through Russia;

I will instead travel to the West Bank in Palestine to make use of my passport and stand in solidarity with Palestinian families in whatever way they need me to. Palestinian communities in the West Bank are current subjects of an active colonial project (settlers burning their trees, stealing their homes, killing them, and the like). The West Bank also happens to be the place where new border technologies are tested: AI tools, drones, camera towers, and such. If we want to resist borders and consequently resist the idea that we can control which people get to go there, we need to resist the occupation.

So: I’ve started learning Arabic and will start my journey to Palestine early September.